Midway through the play, the Chorus makes an appearance on the scene to announce that the tragedy has begun. His speech offers a meta-theatrical commentary on the nature of tragedy. Here, in an obvious reference to Jean Cocteau, tragedy emulates the workings of a machine in perfect order, blithe and automatic in function. The candid and desultory event sets it on its unalterable march: in some sense, it has been lying in wait for its medium. Tragedy belongs to an order outside human time and action. It will advocate itself in spite of its players’ intentions and their attempts at involvement. Many critics refer to the ambivalent nature of this suspense. As noted by the Chorus, in tragedy everything is in the past. The spectator has abdicated, masochistically, to a sequence of events it abhors to watch. Suspense, here, is the period before those events actual realization.

Having compared tragedy to other media, the Chorus then sets it off circuitously, particularly in the mode of melodrama. Tragedy is manifest as docile, cogent and eminent, free of melodramatic stock characters, dialogues, and other confrontations. All these are exigencies and hence inevitable. Thus, in spite of tragedy’s tension, the play acquires a sense of coherence. Further, it gives its players a quality of innocence, which acts as a buttress for them to play their parts. Though Creon will later condone Antigone of portraying him as the villain in her little melodrama, the players are enmeshed in a far more persistent mechanism. Again, what is nuanced and sophisticated is the theory of the tragic and political allegory. The latter is necessarily engaged in the generally academic passing of ethico-politico affectation, the arbitration of innocence, remorse, and responsibility. Though tragic players confront judgment, they do so on their own terms.

The play is also unique in that the inside of the palace ambience is shown. Usually in Greek tragedy all action took place outside of the house or palace depicted on the scene; dire events took place inside, without divulging to the audience. In Antigone, however, the scene was conceived to show Creon finding the body of Eurydice.

Usually in Greek tragedies, the Chorus comprises of a group of ten people, playing the role of death messenger, performing dance and song, and commenting right through from the periphery of the action. Anouilh makes the Chorus a brusque, single figure that retains his collective function and dexterousness. The Chorus does not represent a determinate group, be it the citizenry of Thebes or for that matter the audience. It also appears as narrator, eliciting the tragedy with an introduction and a concise conclusion. In the prologue, it entices the audience and is fully aware itself of the drama: The Chorus also neatly delineates a ritual, entreating the audience on appropriate spectator-ship, so that distractions due to boisterous behavior are reduced. The Chorus appears repeatedly through the play, marking the denouements and efficaciously interceding into action.

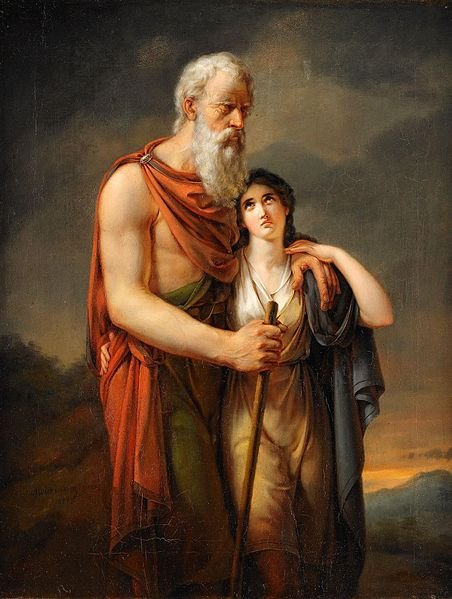

Antigone’s insistence on her desire makes her appear boorish and brash. At the same time, such qualities are what make her beauty a tragic one. Antigone alleges this beauty throughout her discomfit relationship with Creon. Especially, Oedipus emerges as its representation. Oedipus’ moment of beauty comes at his moment of total despair and abjection, the moment when he knew all and had lost any hope whatsoever and passed way beyond the affable and affluent past of his. Like Oedipus, Antigone will become beautiful when she will also be totally emaciated. Antigone’s beauty is somehow an enigma in itself.

Some critics have interpreted Antigone as a figure “between two deaths,” what we will refer to here as her fall as a social entity and her death as her demise. The space between two deaths is captured by her tomb, the appalling dungeon in which she, as an alienated and abject body, so as to blight her delinquent vibes polluting the city. Her death sentence makes her bleaker than animals; such is her “Oedipal” beauty, a beauty in her state of abjection. As she appears to sense, even amid clouds of dejection, she will not die alone. Her tomb will also serve as her bridal bed, Antigone finally bringing Haemon with her to the “bridal bed”. Interestingly, another victim of the tragedy – Queen Eurydice – also meets her end another dilapidated tomb that doubles as a bridal bed. Eurydice dies in her bedroom—amid familiar, comforting feminine acclimations, as a maiden queen of sorts, as the same person that first spent a night with Creon. The wound in her neck appears all the more caustic in this context. It could then be adjourned, that her death is all the more tragic because she dies with all her bombastic feminine purity intact.

To arbitrate, the Antigone indisputably belongs to the best works of Sophocles; indeed, most modern critics place it above Oedipus the King. The Antigone, must be received with empathy as the canon of ancient tragedy; no tragedy of antiquity assimilates pure idealism and equanimity of artistic development as it does. It is the first poem produced by the collaboration of the various drastic resources of which tragedy was capable and could be articulated with; of all the extant works of Sophocles it is the one without a trace of defect; no other exhibits such an exemplary aggregation of subject, language and technique with aesthetic appeal. Its greatness lies in its perfect regularity of discourse, its ideas which are exalted but not esoteric, its real and agile characters–qualities brought to perfection by eclectic embellishment of dialogues and odes that are truly elite.