The Spartans, who formed the bulk of the defending Greek forces, were all killed. Outnumbered by the Persian soldiers, the Spartans must have known the impending doom in advance. Yet, they displayed exemplary loyalty and carried on the defense of Thermopylae. Though Thermopylae was eventually lost to the Persians, the valor displayed by the Spartans proved to be an inspiration for the Greek soldiers. In this spirit, the Greeks did gain some lost ground in battles that were to follow, albeit on a smaller scale. (Cartledge, p.45)

The Persians were led by Xerxes. He led his fleet of battle ships from the coasts of northern Greece into the Gulf of Malia. The mountainous terrain along this coast acted as a natural fort for Greece. The only way the invaders can capture the Greek capital was by accessing the Thermopylae pass. This fact was understood by both the opposing forces, and hence made great efforts to hold this important passage across the mountains.

Xerxes’ reading of his challenge was quite accurate. He knew that he needed a large army of soldiers to tire, dent and eventually overwhelm the Spartan soldiers. So he assembled his army from across the length and breadth of what was a sprawling Persian empire. The end result was a mammoth gathering of soldiers that was 2.6 million strong. This figure does not include the men involved in support operations like ship crew, etc. It could be asserted that the battle was decided by this single factor – the number of men in confrontation on both sides. The Spartans were simply outnumbered and hence out-matched. Yet it is not for the ultimate result that the Greeks who lost their lives be remembered. It is for the way they marched ahead fully cognisant of their fates. (Cartledge, p.65)

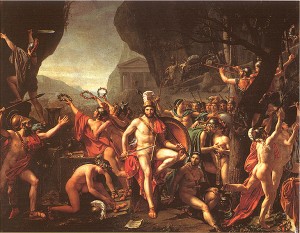

The defending Spartans were led by an equally competent Leonidas, who was the King as well as the General. The primary objective of Leonidas was to keep the Persians away from stationed Greek navy. Leonidas believed that if his forces can engage the Persians at thermopylae for a long enough time, they would have to eventually retreat when their food supplies run out. Yet, Leonidas was not oblivious to the overall superiority of the Persians. He knew that only an inspired effort from his men can achieve this objective, upon which much is at stake. (Englewood, p.110)

It was a tradition in Sparta to pay homage to their martyrs in the way of ceremonies and special rituals. The whole citizenry would participate in such events and it was an integral aspect of Greek culture. But sadly for Leonidas, such symbolic reverence after death could not be accorded. It was only by chance that his body was identified and recovered in a decomposed state forty years after his death. (Englewood, p.115)

The battle lines have been drawn. The Greek civilians held their breath as a weak army marched off toward Thermopylae. In the first day of fighting, the Greek strategy was to ambush Persian infantrymen in what might be called a shock-and-awe tactic and quickly retreat to their hideouts. This tactic was successful for this day. So Athens was still safe. The second day of combat followed much the same pattern. The Greeks succeeded in keeping Persians at bay for a second time in a row. It is difficult to guess how long this pattern could have been sustained. However, such a speculation is made irrelevant by an interesting turn of events. At this juncture, a Greek named Ephialtes brought about a decisive turn to the state of affairs. Though he was a Greek, he betrayed his fellow countrymen and disclosed to the Persians the whereabouts of an alternative pass to get at the Greek navy installations. This alternative pass was called Anopaia. (Maurice, p.69)

Leonidas put together some of the most skilled Spartans and formed a battalion of 300 soldiers. The neighboring kingdoms of Thespiae and Thebes were allied with Greece, but their contribution in terms of men on the battlefield was marginal. This army of a few hundred individuals was confronted by a 10,000 strong Persian troop. Yet, the bravery of the Greeks was such that they fought themselves to death. In the final analysis, the Greeks were successful in keeping the Persians engaged in the battle of Thermopylae so that the rest of the Greek army can find refuge. (Englewood, p.136)

Of all these brave men who laid their lives for their King’s honor, Dieneces’ exploits in the battleground were legendary and have become an integral part of Greek history. Other players in this historic drama were Themistocles and Eurybiades. In collaboration with the Spartan leader Eurybiades, Themistocles convinced the Greek administrators to devote their new found wealth (that transpired as a result of newly discovered silver mines) to the strengthening of the naval fleet. This development did not really help Greece in its defense of Athens from the Persian forces. If anything, Themistocles’ love of power and authority undermined the Greek defense. For this reason, Themistocles does invited criticism from many Greek historians. (Maurice, p.45)

The brave army of men led by the illustrious Leonidas could not sustain the unrelenting aggression from Xerxes’ men. The inevitable finally happened when the Spartan army was forced to retreat from the Thermopylae pass. While the remaining Spartan army were able to escape inland, the Theban allies were not so lucky. They were rounded and captured by the opposing forces. Leonidas was also to meet a similar fate. The exact nature and time of Leonidas’s demise is not known. It was believed by historians that he may have tortured and killed on Xerxes’s instructions. (Kraft, et.al., p.186)

The battle of Thermopylae holds a lot of historical significance. In what transpired to be a highly symbolic combat, the equations of power and dominance around the Mediterranean Sea were to change. According to historian David Frye,

“Persia represented the old ways — a world of magi and god-kings, where priests stood guard over knowledge and emperors treated even their highest subjects as slaves. The Greeks had cast off their own god-kings and were just beginning to test a limited concept of political freedom, to innovate in art, literature and religion, to develop new ways of thinking, unfettered by priestly tradition. And yet, despite those fundamental differences, the most memorable battle between Greeks and Persians would hinge on less ideological and more universal factors: the personality of a king and the training and courage of an extraordinary band of warriors.” (Frye, www.historynet.com)

The war was not based on a spontaneous decision by either side. There were years of growing tension between the two sides. In the decades leading up to the time of this war, both the Persian and Greek kingdoms were experiencing internal unrest. The ruthless and oppressive nature of these two regimes caused increasing discontent among the subjects. More importantly, the cultural differences between the two sides seemed irreconcilable. The Greeks deemed the Persians as an inferior race of people, who have to be enslaved and ruled over. The Persians wanted to take revenge for the wrongs done to them by Greeks in the past. So in this atmosphere of mistrust and contempt, the breaking out of the war was just the final but inevitable episode. (Englewood, p.121)

Hence, the battle of Thermopylae assumes a special significance in that it had very broad implications. In the final analysis, it is not the loss of men or loss of territory that defines this battle. To the contrary, it is the resilience and courage with which a thoroughly outnumbered team of men marched to Thermopylae and into history books.

Works Cited:

Frye, David., Greco-Persian Wars: Battle of Thermopylae By David Frye www.HistoryNet.com, accessed on 21st October, 2007.

Stewart, Zeph., The ancient world: justice, heroism, and responsibility.

Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall, first published in 1921, reprinted in 1966.

Cartledge, Paul., Thermopylae : The battle that changed the world , Woodstock, NY : Overlook Press, 2006.

Kraft, John C., Rapp Jr, George, Szemler, George J., Tziavos, Christos., Kase, Edward W., The Pass at Thermopylae, Greece Journal of Field Archaeology > Vol. 14, No. 2 (Summer, 1987), pp. 181-198

Maurice, F., The Size of the Army of Xerxes in the Invasion of Greece 480 BC, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 1930 – JSTOR, accessed on 21st October, 2007