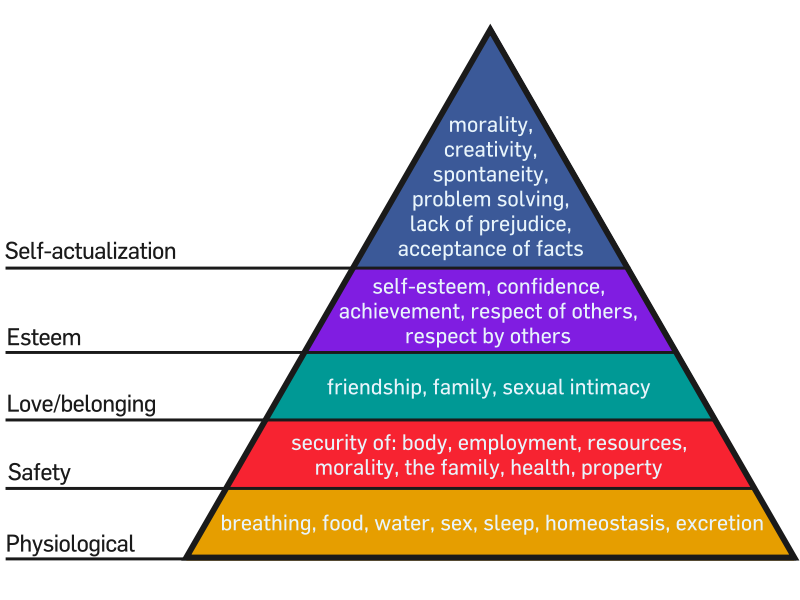

The article explains Maslow’s theory thus: an individual grows and develops his/her personality in accordance with a specific hierarchy of needs. The stages in the hierarchy are physiological needs, safety/security needs, love and belongingness needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization needs; strictly in that order.

This concise statement of the theory is fairly well grounded and does not yield to critical analysis, but the following assertion does raise a few questions.

“According to Maslow, these needs occur in the order presented–beginning with physiological needs and ending with self-actualization needs. A person does not move on the next level until the previous need is fairly well satisfied.” (Quick 1991)

It is the above quotation from the article that will be scrutinized at length in the following pages.

A crucial problem with Maslow’s approach is its focus on the personal development of the individual and that social connections are marginal in Maslow’s theory. It is seen in the hierarchy of needs that social necessities like love, esteem, prestige and status, are relegated to stages three and four and do not find a mention in the final category – self actualization. According to Maslow, the social needs are essential stepping stones to the top of the hierarchy, but the eventual goal for the individual is realization of his/her potential. For persons that are self-sufficient enough to be able to realize their self, the lower level needs as love and esteem apply as deficiencies and leave them with the freedom “autonomous fulfillment”. The inconsistency is raised by the feminist theory which places very high value on the relatedness of women, but which in Maslow’s framework is seen as a deficiency to be conquered. (Trigg 2004)

More questions can be raised about the synthesis between Maslow’s hierarchy and the widespread critique of consumerism. For example, the theory’s relationship to the new “hierarchy of consumption” is yet to be elucidated. What is also unexplained is how and social needs operate in the hierarchy of needs. Do individuals will move from the third stage of social need, belongingness to the next one of self-esteem, and if successful onto the ultimate stage of self-realization. Trigg puts forward this consideration:

“Since the individual is unable to progress without satisfying each category of need in the hierarchy, then it logically follows that lexicographic preferences will apply at these higher points in the hierarchy. If lexicographic preferences are no longer relevant, but the hierarchy of needs is still in place, however, then how is the ordering of needs designed in the new Post Keynesian theory of consumption? And in more general terms, is the individual still the basic unit of analysis, or has the analysis moved onto a qualitatively different plane in which priority is given to social relationships?” (Trigg 2004)

Another criticism of the concept of self-actualization is its failure to take into account the process of learning in the context of human evolution. It is important because learning is crucial in any adaptation of the hierarchy of needs. This also influences the corresponding branch of the Post Keynesian synthesis. Higher economic status lead to broader choices to consumers, as they graduate away from the basic physiological imperatives. Consumer demand increasingly becomes a result of their knowledge and less so a result of their instincts.

The most important confrontation to Maslow’s concept had been offered by Bourdieu, whose social theory offers an alternative foundation for a social critique of consumerism and for the evolutionary theory of consumption. Bourdieu offers a class-based approach in which the role of cultural capital assumes most significance. For those in the lower strata of the social hierarchy, culture has a major influence over consumer expenditure, holding back the response of consumption to changes in income. In search of elevated aesthetic experiences, those with higher cultural capital modify their spending on luxury goods. This new structure not only constrains the consumption of lower social strata and leads to small, less obvious, consumer behavior at the top. This is in sharp contrast to Maslow’s proposal and its argument is well grounded too. (Trigg 2004)

In another allegorical exposition of Maslow’s theory, Deborah Bice and Courey Tamra argue that there is a conscious, systematic method that people adopt to reach the state of self-actualization. In the novel Frankenstein, the monster created by Dr. Frankenstein starts at the lowest level – physiological. Right through his life he tries to reach a higher stage, say, love and belongingness, but falls short for feelings of insecurity. The authors offer a different view point to Maslow’s concept of self-actualization by analyzing the struggles that the monster endures. Since the monster is neglected and left to fend for himself right from birth, he has great difficulty to cater to his own basic needs. But cravings for food, water and sleep are so instinctive that he somehow manages to acquire some basic skills. This is in contradiction to Maslow’s presumption that the basic needs can be fulfilled only with the assistance of other humans. The monster defies this constraint and manages to survive, which is a proof of his quest for higher states of existence. (Bice & Tamra 2003)

The authors further argue that once the physiological needs stage is successfully met the monster gains awareness of his isolation. His curiosity leads his to try and interact with other people, which is why he finds a hut where he can live. In spite of strong opposition, first from the owners of the hut and later from the villagers, he prevails in finding him a home. The circumstances of his life, in the end, make his longing for safety and security a life long effort.

“Upon observing a family, he sees safety and love, and now desires them. Through the monster’s observation of the family, he actually begins to feel the safety need. Even though he never joins them, he began to think of them as his own. He considers the hovel his home, and he also falls into a regular routine. So, on some level, although minimal, he may have touched on the second level, but it is by no means ever attained.” (Bice & Tamra 2003)

Though the monster never ultimately reaches the phase of self-actualization, it is worth noting that his behavior mimics the behavior of one who has reached that stage. Moreover, he displays signs of autonomy, creativity and problem-centered motivation, which are characteristics of self-actualization. So in the final analysis, the allegorical interpretation of the character of the monster in the novel Dr. Frankenstein forces us to rethink the presumptions upon which Maslow’s theoretical framework is built. (Bice & Tamra 2003)

Further criticism of the concept of self-actualization could be presented upon sifting through the biography of the author of the novel. Mary Shelley, the author of Dr. Frankenstein had a tough childhood herself. Her mother dies in childbirth and her step mother was not very kind towards her, which meant that though her basic needs were met, she never really received genuine affection. It could hence be induced that as a child, Mary Shelley was deprived of needs across all levels of the Maslow’s hierarchy.

Her choice of an already married Percy Bysse Shelley for a lover, and the subsequent eloping of the couple is typical for her circumstance. Bice and Tamra assert that,

“the fact that at age fifteen she chooses to leave home and ‘travel’ with Shelley supports her struggle with security, comfort, and structure at a very young age; however, Maslow’s safety and security needs that were previously lacking as a child may have been provided in this union between Shelley and Mary. Mary actually achieves Maslow’s higher levels of love and belonging needs. In fact, this may have been the very first time in her life she has moved beyond the lower level needs and feels true affection from another human being. Not only is Mary receiving affection from her husband, but she is also offering affection to her first-born son, William. And although realization of self-actualization, Maslow’s highest hierarchal level, is a possibility at this point in Mary’s life, attaining these higher levels is quickly shattered by the subsequent turn of events” (Bice & Tamra 2003)

In the end, one might conclude that Mary Shelley reaches Maslow’s level of self-esteem while experiencing satisfaction for achieving success and recognition for her novel. It would seem that throughout Mary’s life, although she transcends from one level of Maslow’s hierarchy to another, she never fully satisfies all needs at each level. We should also note that self-actualization, in her case was unlikely, as she remained in isolation and despair for the rest of her life. Thus Maslow’s concept of self-actualization requires a pedagogical as well as contextual re-examination.

References:

Quick, Thomas L. (May 1991), “An HRD refresher. (human resource development) (list of social science scholars contributing to the foundation on which occupational training theories are based).” Training & Development 45.n5 : 74(2).

Trigg, Andrew B. (Sept 2004), “Deriving the Engel curve: Pierre Bourdieu and the social critique of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.” Review of Social Economy 62.3 : 393(14).

Bice, Deborah, and Tamra Courey., (Summer 2003), “Frankenstein Meets Maslow.” Academic Exchange Quarterly 7.2 : 40(4).